Alkimos beach (Source: http://www.perthnow.com.au/news/western-australia/new-coastal-city-to-be-built-over-next-25-years/story-e6frg13u-1225821595518)

Essential Environmental is currently gearing up for a new series of coastal projects based in the Shire of Northampton and closer to home, in the coastal node of Alkimos in the north of Perth. This work will build upon the coastal experience Essential Environmental has already gained from the coastal and flood assessments, and foreshore management plans undertaken for Point Samson, Gnoorea, Karratha and Roebourne, in the Pilbara, as well as in Lancelin, in the last year.

Our team will be undertaking the Kalbarri Foreshore and Coastal Management Plan Review and the Horrocks Beach Coastal Plan Review which will assist the Shire of Northampton respond to changing environmental and recreational pressures, strategic planning recommendations and changes in coastal management policy, particularly State Planning Policy 2.6 – State Coastal Planning.

Essential Environmental will also prepare a CHRMAP for the proposed coastal development at Alkimos, approximately 40 km north of the centre of Perth.

What is a CHRMAP you may well ask (and good luck if you can pronounce it)? CHRMAP stands for:

Coastal Hazard Risk Management and Adaptation Plan

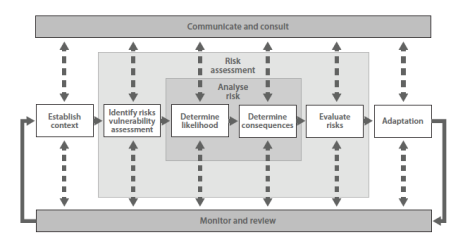

The process of developing a CHRMAP is intended to ensure an appropriate risk assessment and management planning framework is used to incorporate coastal hazard considerations in land development decision-making processes. The primary focus is to ensure a robust risk assessment process is used to identify adaptation measures required to respond to coastal hazards, and to set up an appropriate framework for the monitoring and review those outcomes.

Such planning processes are becoming more critical to Australia where more than 85% of the population live within 50km of our coasts and as the impacts of climate change and sea level rise upon our coastal towns increase. This is acknowledged by the State Government in their State Planning Policy 2.6 – State Coastal Planning policy which requires development to be protected from coastal processes by allowing for sea level rise and for setbacks to be based on the mean of the median model of the latest Assessment Report of the IPCC Working Group.

State Government policy SPP 2.6 identifies that coastal foreshore reserves should be “set aside in public ownership to allow for likely impacts of coastal hazards and provide protection of public access, recreation and safety, biodiversity and ecosystem integrity, landscape, visual landscape, indigenous and cultural heritage.” However, the policy also recognises that development still may need to occur in areas which are likely to be impacted by physical processes if the community is to have good access to amenities next to our beaches, such as changerooms, surf-lifesaving clubs and playgrounds.

An example of an outcome of a CHRMAP process might be the identification of an attractive area of coastal foreshore which is currently not at risk of being impacted by processes such as storm surge or erosion, and may be a great spot for some BBQs, public toilets and a playground. However, some clever scientist/engineer who has undertaken coastal process modelling of the area has identified that this same area of foreshore is likely to experience erosion in 100 years time and therefore infrastructure and the community would be at risk at some stage in the future. Once this risk has been identified, those responsible for managing the foreshore use this information to make a decision as to how they will adapt to this expected change. Options might include:

- Not put anything in that area of foreshore at all and remove the risk all together

- Install toilets/BBQs/playground there now and identify another area of foreshore to which it can be moved when erosion starts becoming a real hazard

- Be prepared to construct a sea wall or groin near that area of foreshore to protect foreshore infrastructure into the long-term

There are a number of other issues that need to be considered to ensure that a CHRMAP is useful and practically implemented. This includes; how changes in coastal processes will be monitored, how and when will monitoring information will be used to inform management of coastal foreshore areas, are the necessary adaption options realistic/viable, and has enough area within the foreshore been reserved to accommodate any changes that might be identified from the monitoring process.

City Beach foreshore, Perth (Source: http://perthbritannia.com/images/Sceneary/City%20Beach%20Perth.jpg)

The need for effective coastal planning is particularly relevant in the context of the release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Impacts volume of the Fifth Assessment Report, released last week, which has identified that the need to focus on managing risk and adaption planning associated with sea level rise and extreme weather events has increased in recent years. Specifically, a key risk identified by the IPCC in this report is:

“Risk of death, injury, and disruption to livelihoods, food supplies, and drinking water, in addition to loss of common-pool resources, sense of place, and identity, due to sea-level rise, coastal flooding, and storm surges affecting high concentrations of people, economic activity, biodiversity, and critical infrastructure in low-lying coastal zones and small island developing states.”

This is hardly something we can ignore as a largely coastal-living country and our coastal planning will have to continue to adapt if we are to minimise these risks into the not-so-long-term.

Coastal erosion at Wamberal beach, New South Wales, in 1978 (Source: Geoscience Australia http://www.ga.gov.au/ausgeonews/ausgeonews201103/climate.jsp)